To be Born Great, Achieve Greatness, or have “Greatness Thrust Upon Them”: Considering Handel and the Trope of the Great Composer

Par Emma Cameron

Introduction

The introductory chapter of Kate Molleson’s recent study of ten marginal twentieth-century composers articulates the following aim:

|

I’m not interested in making new heroes, or trying to puff up new hagiographies or invent new canons…These composers aren’t alternatives to any others, because the word ‘alternative’ suggests an incontrovertible core. They seek to replace nobody, but they deserve to be heard (Molleson 2022, 5).

|

Molleson’s book exemplifies a recent trend in the study of music, arguably prompted by the introduction of feminist, postcolonial and other frameworks into music scholarship. This trend seeks to introduce voices representing a wide variety of musical traditions into the conventional canon of Western European art music. While such scholarship is illuminating and reveals unexplored areas for future study, the role remaining for the so-called great composers of the traditional canon remains a subject of contention: as Molleson notes, there is an “odd and spurious fear that the Great Works… are somehow threatened if classical music becomes more inclusive” (Molleson 2022, 5). But, as Molleson stresses, “nobody is mooting that we should ditch Mozart or Mahler. Nobody is suggesting that their music doesn’t speak for our times and for all time” (Molleson 2022, 5). Like Molleson, I maintain that the great composers remain an integral component of a far-reaching music history.

|

Yet reexamining the biographies of these composers also reveals new perspectives. I suggest that considering scholarship which uses alternative frameworks to address the lives, oeuvres, and legacies of the masters has the potential to refine perceptions of these musical artists and their works. This paper considers examples of biographical scholarship on the unmistakably canonic composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) by David Hunter and Suzanne Aspden, who employ historiographical lenses to offer alternate framings of Handel’s life and work. The use of such scholarship in the music history classroom will not only reveal new historiographical perspectives, but could topple the ideal of the great composer.

|

Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood. "Handel: Rinaldo, Act 1 - Overture." ℗ Decca Music Group Limited, 2000. YouTube video. Handel: Rinaldo / Act 1 - Ouverture

|

The issues with composer biography

Appreciating the origins of the great composer ideal is an important preliminary step to understanding the issues surrounding composer biography. As Christopher Wiley notes, most composer biographies were initially developed by nineteenth-century historians (Wiley 2008, 3). Therefore, they contain tropes that reflect the literary writing style and societal ideals of the time, including the concept of the “exemplary life,” which champions the composer as a “paragon of professional and moral conduct” (Wiley 2008, 3). This ideal served the aim of educating and inspiring the reader, but it also invested purportedly objective accounts with a hagiographical tone (Wiley 2008, 3). To varying extents, the tropes present in these nineteenth-century narratives have been perpetuated in subsequent accounts of composers’ lives, although they have been challenged in recent studies of musical biography.

Hunter: re-investigating early biographies

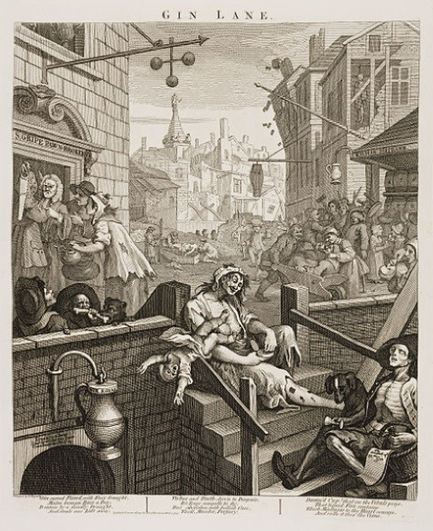

Figure 2: William Hogarth’s well-known painting Gin Lane is a stark

Figure 2: William Hogarth’s well-known painting Gin Lane is a stark depiction of crime in eighteenth-century London.

William Hogarth, Gin Lane, 1751, etching and engraving,

13.8 x 12” (35 x 30cm), Royal Academy of Arts, London.

One such study has been conducted by David Hunter, who grounds his examination of Handel in contemporary general histories of music by Charles Burney (c.1776) and John Hawkins (1776). Four themes common to both these histories support the depiction of Handel as a great composer: financial success in a free market; “unbelievable strength”; independency; and a “sin-free life” (Hunter 2015, 332). Addressing each of these themes in turn, Hunter draws on the wider political, economic and social contexts of eighteenth-century Britain to undermine the mythical portrait they suggest, presenting an alternate narrative of Handel’s success based upon the need for a figurehead for the “Protestant, liberty-loving, entrepreneurial ideology” of contemporary Britain (Hunter 2015, 349).

Having considered these themes, Hunter turns to the 1711 opera Rinaldo to show how narratives of commerce, genius and success are foregrounded in a musical work. Through evaluation of the commissioning, composition, performance, audience reception and publication of the opera, Hunter demonstrates how Hawkins’ and Burney’s accounts of these events invest them with a significance that contributes to Handel’s mythical character. By interrogating Handel’s accepted status as a great composer, Hunter highlights musicology’s unquestioned acceptance of canonic composers, and encourages study into untold and overlooked narratives in the lives of these individuals.

Having considered these themes, Hunter turns to the 1711 opera Rinaldo to show how narratives of commerce, genius and success are foregrounded in a musical work. Through evaluation of the commissioning, composition, performance, audience reception and publication of the opera, Hunter demonstrates how Hawkins’ and Burney’s accounts of these events invest them with a significance that contributes to Handel’s mythical character. By interrogating Handel’s accepted status as a great composer, Hunter highlights musicology’s unquestioned acceptance of canonic composers, and encourages study into untold and overlooked narratives in the lives of these individuals.

|

In contrast to Hunter, Suzanne Aspden approaches Handel’s towering cultural status in eighteenth-century England from a social perspective, investigating the relationship between the seemingly disparate public and private domains of musical performance during this time. She suggests that the increased technical and social accessibility of Handel’s music between 1730–50 enabled his works both to be played more frequently in public venues, and to be executed by amateur performers in private settings. Such increased performance resulted in widespread familiarity, contributing to the composer’s fame.

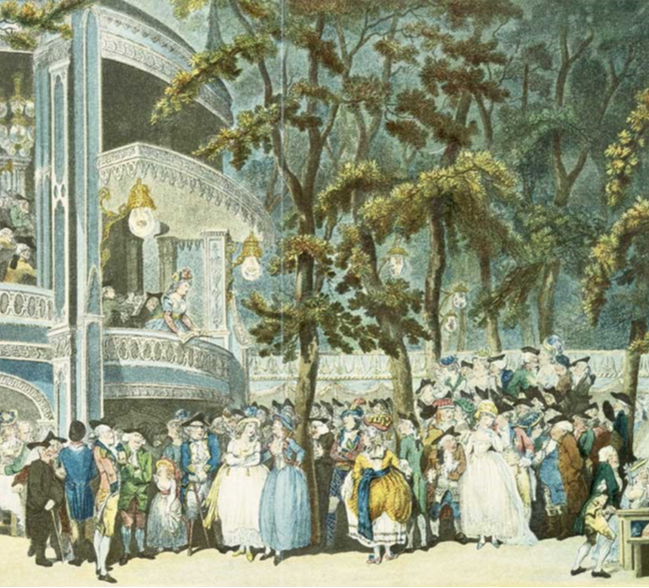

As well, Aspden notes that economic factors influenced Handel’s celebrity: the rapidly expanding market for music ensured his compositions were disseminated among a wide audience that spanned further social boundaries, such as gender and social status. Aspden notes Handel’s own role in the decision to address his music to the upward-aspiring merchant class through his oratorios, which blended “exclusive and popular musical forms,” and through the performance of his music in genteel public settings such as Vauxhall Gardens (Aspden 2017, 213). |

Both the accessibility and performability of Handel’s work, and the commercial marketplace that disseminated it across a wide geographic area, ensured the composer and his music became known across England. This dissemination contributed to a familiarity that earned Handel the title of great composer. Through Aspden’s social and economic analysis, it is apparent that to some extent Handel’s reputation as a great composer and a national hero was in part a result of his ability to market his music to a wide audience. Although they employ contrasting approaches, both Aspden’s and Hunter’s scholarship challenges the ideal of the great composer.

The historiographical, economic and social lenses employed by Hunter and Aspden reveal new insight into the narrative of Handel’s life and the success of his works. Far from “ditching” Mozart or Mahler, paying attention to marginalized composers asks scholars to listen more attentively to existing voices in the canon, nuancing our understanding and appreciation of the great composers and their works. Through consideration of such scholarship in the music history classroom, the nineteenth-century ideal of the composer as a genius is challenged, opening the conventional Western European art music canon to new voices.

Bibliographie

ASPDEN, Suzanne. 2017. “Disseminating and Domesticating Handel in Mid-Eighteenth-Century England.” In Beyond Boundaries: Rethinking Music Circulation in Early Modern England, edited by Linda Phyllis Austern, Candace Bailey and Amanda Eubanks Winkler. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 207–222.

HUNTER, David. 2015. “Nations and Stories.” In The Lives of George Frederic Handel. Rochester: Boydell and Brewster, p. 332–392.

MOLLESON, Kate. 2022. Sound Within Sound: Opening our Ears to the Twentieth Century. London: Faber & Faber.

WILEY, Christopher. 2008. “Re-Writing Composers’ Lives: Critical Historiography and Musical Biography”. Dissertation. London: Royal Holloway, University of London, 612 p.

HUNTER, David. 2015. “Nations and Stories.” In The Lives of George Frederic Handel. Rochester: Boydell and Brewster, p. 332–392.

MOLLESON, Kate. 2022. Sound Within Sound: Opening our Ears to the Twentieth Century. London: Faber & Faber.

WILEY, Christopher. 2008. “Re-Writing Composers’ Lives: Critical Historiography and Musical Biography”. Dissertation. London: Royal Holloway, University of London, 612 p.