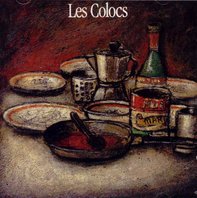

Les Colocs, 1993:

Class-Conscious Quebec Music

par Charlotte Malischewski

My mother came to pick me up from school one afternoon in the spring of fifth grade and told me that the lead singer of Les Colocs, André “Dédé” Fortin, had committed suicide. He had lived around the corner from where we were living so my mom suggested we lay a flower at the foot of his apartment door. I distinctly remember noticing the many flowers and candles from fans who had already paid their dues and feeling taken by how he and his music had touched those around us. Many years later, I return to the album that started it all to better understand its context and influence. By looking at the historical context and the band’s story as well as the production, reception, and impact of their debut album, I argue that Les Colocs introduced a new kind of class-consciousness into Quebec's popular music.

Context

Chanson has long played an important role in the imagining and affirming of a Quebec national consciousness (Roy, 1991, p. 12). From La Bolduc and Félix Leclerc – sometimes referred to as the “mother” and “father” of Quebec's song – to the chansonniers of the Quiet revolution, music helped tell the stories of Quebec and contributed to a common narrative (Ledoux, 2010 p. 13). From the late 1960s, many in the francophone music scene used their platforms to promote René Lévesque’s separatist political party, the Parti Québécois (hereafter “PQ”) who were eventually elected in 1976. Though some remained active in the PQ, with the prospect of a referendum on the question of Quebec’s independence looming, many began to distance themselves from the increasingly moderate views the party presented. In the wake of the 1980 referendum defeat and the subsequent break up between the PQ and public sector unions, this distance grew and widespread disaffection set in. Some musicians gave up their francophone political music, some began to make music in English, and others quit altogether. The discourse of “Quebec identity” gave way to anglophone music, from the United States in particular. It was not until the end of the first half of the 1990s that Quebec chanson came back to the fore and it did so in the midst of a dearth of commercially successful francophone music in Quebec.

Though many would define themselves as Quebecois, younger generations, like those who would form Les Colocs, could also see the effects of petty bourgeois indifference in the disconnect between those who benefited from the Quiet revolution and the “ordinary” folk of Quebec. In the early 1990s, there was no electoral legitimacy that was explicitly anti-poverty, and central Montréal was marked by gentrification and a decline in social services. Younger generations who lived through the suburbanization of Quebec were rejecting the compromises the previous generation had made and were consciously engaging with those from different cultures and parts of the world who were now calling Montréal home. The hope of a singular shared reality of the 1980s gave way to a generation for whom sovereignty was not the only concern and whose class-consciousness extended to a critique of the nationalist project (Sweeny 2015). It is of this era and with this consciousness that Les Colocs (meaning “the roomates”) were born.

Though many would define themselves as Quebecois, younger generations, like those who would form Les Colocs, could also see the effects of petty bourgeois indifference in the disconnect between those who benefited from the Quiet revolution and the “ordinary” folk of Quebec. In the early 1990s, there was no electoral legitimacy that was explicitly anti-poverty, and central Montréal was marked by gentrification and a decline in social services. Younger generations who lived through the suburbanization of Quebec were rejecting the compromises the previous generation had made and were consciously engaging with those from different cultures and parts of the world who were now calling Montréal home. The hope of a singular shared reality of the 1980s gave way to a generation for whom sovereignty was not the only concern and whose class-consciousness extended to a critique of the nationalist project (Sweeny 2015). It is of this era and with this consciousness that Les Colocs (meaning “the roomates”) were born.

The band's story

Les Colocs’ story can be traced back to 1990 when Dédé Fortin, originally from Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, moved into the third floor of the now famous 2116 Boulevard St. Laurent in Montréal. The initial lineup consisted of Dédé Fortin, Louis Léger, Marc Déry, and Jimmy Bourgoing from Quebec as well as Patrick Esposito Di Napoli from French Catalonia, but Déry and Léger soon left. The band placed an ad for a bassist in the newspaper Voir and found Quebecois Serge Robert. Esposito’s friend Mike Sawatzky, a Cree from Saskatchewan, also joined the group. Those five members became the original Les Colocs.

Following a number of smaller performances for those around them, Les Colocs made its first splash at the Festival international de rock de Montréal in 1990. They continued to play live and developed a following with performances at Café Campus, Le Clandestin, Les Bobards, Les Foufounes Électriques, and Le Quai des Brumes, which became their home venue. As early as March 1991 the newspaper Le Soleil was comparing Dédé Fortin to the likes of Plume and Jean Leloup for his songwriting, though Fortin was adamant about the fact that Leloup’s music was different and had not influenced him. That year, they reached the semi-finals at the Festival international de la chanson de Granby and, in 1992, they played at the Festival d’été de Québec. The following winter, the band entered the Empire des futures stars, a talent contest that promised a record deal as its prize, but which Bourgoing explains was largely about getting a chance to play Club Soda for those in the band (Musimax 2001). Though they were favored to win, a technical issue arose from the fact that group had not signed a contract before performing in the contest and so they were disqualified. On May 5, 1992 Le Devoir featured a quote from Fortin saying that he would have signed the contract had he had a pen in his hand (Bilodeau 1999). Interestingly, a documentary that aired on Musimax tells a different story. Denis Grodan, the show’s artistic director, explains that the contest carried with it an exclusivity agreement that would prevent the band from organizing their own shows or recording for at least six months. Bourgoing added that with Esposito dying of AIDS and present in Canada only on a three-month visitor visa, the band felt a sense of urgency and the decision not to sign the contract was a conscious one informed by the man who would be become their manager, Raymond Paquin. With the band now free from the sponsorship framework of the competition, Paquin approached BMG and Les Colocs signed with them on May 20, 1992.

Following a number of smaller performances for those around them, Les Colocs made its first splash at the Festival international de rock de Montréal in 1990. They continued to play live and developed a following with performances at Café Campus, Le Clandestin, Les Bobards, Les Foufounes Électriques, and Le Quai des Brumes, which became their home venue. As early as March 1991 the newspaper Le Soleil was comparing Dédé Fortin to the likes of Plume and Jean Leloup for his songwriting, though Fortin was adamant about the fact that Leloup’s music was different and had not influenced him. That year, they reached the semi-finals at the Festival international de la chanson de Granby and, in 1992, they played at the Festival d’été de Québec. The following winter, the band entered the Empire des futures stars, a talent contest that promised a record deal as its prize, but which Bourgoing explains was largely about getting a chance to play Club Soda for those in the band (Musimax 2001). Though they were favored to win, a technical issue arose from the fact that group had not signed a contract before performing in the contest and so they were disqualified. On May 5, 1992 Le Devoir featured a quote from Fortin saying that he would have signed the contract had he had a pen in his hand (Bilodeau 1999). Interestingly, a documentary that aired on Musimax tells a different story. Denis Grodan, the show’s artistic director, explains that the contest carried with it an exclusivity agreement that would prevent the band from organizing their own shows or recording for at least six months. Bourgoing added that with Esposito dying of AIDS and present in Canada only on a three-month visitor visa, the band felt a sense of urgency and the decision not to sign the contract was a conscious one informed by the man who would be become their manager, Raymond Paquin. With the band now free from the sponsorship framework of the competition, Paquin approached BMG and Les Colocs signed with them on May 20, 1992.

The debut album

In September 1992, they then began working on what would be their self-titled debut album. The recording was completed in a mere three weeks. Though eight of the songs would be Fortin’s own or co-writes, the album was much more than a solo project. Two saxophonists, a trombone player, a trumpeter, a fiddler, and a whole crew of gumboot dancers known as La Famille Botte rounded out the album. During the recording, Fortin insisted that Esposito and Robert each get to sing one of their songs on the album and, on the day of the album release, Fortin refused to do promotional interviews until BMG would agree to pay at least fifty dollars to all the backup singers and dancers performing that night (Musimax 2001). That sense of community and equality was all the more explored in the lyrics and music of the album.

The album presents a collective, rhythmic energy around building a better society that is articulated in the language of the everyday. The lyrics are imbued with the cynicism of the lower class experience and explore the realities of broken homes, troubled youth, suburbanization, consumerism, AIDS, and low self-esteem, all with a touch of politically-conscious irony and self-deprecating humour. Each of the album’s ten tracks tackle a different topic, a different perspective, and sound quite different from one another, but the socio-political consciousness of the lyrics and the engaging and uplifting sound of the music lend the album a certain coherence.

The album presents a collective, rhythmic energy around building a better society that is articulated in the language of the everyday. The lyrics are imbued with the cynicism of the lower class experience and explore the realities of broken homes, troubled youth, suburbanization, consumerism, AIDS, and low self-esteem, all with a touch of politically-conscious irony and self-deprecating humour. Each of the album’s ten tracks tackle a different topic, a different perspective, and sound quite different from one another, but the socio-political consciousness of the lyrics and the engaging and uplifting sound of the music lend the album a certain coherence.

Once asked about the album’s musical influences, Fortin cited everything from rockabilly, funk, rap, blues, jazz, and zydeco to French songs and waltzes, even mentioning Quebec folk supergroup La Bottine Souriante (Paquin 2004, p. 33). The album is thus a mix of those influences and the diverse lived experiences of the members of the group, some of whom were enrolled in school like Robert and others of whom were metro musicians living hand to mouth like Esposito. The album’s undeniable dance-ability makes it possible for different listeners to engage with it at different levels: some just looking for fun and entertainment might lose themselves in the music while others looking for meaning might find it in the socio-political commentary of the lyrics.

The album's cover art also reflects its origins. A simple black and white photo of the band sitting around eating dinner is featured on the back while the cover art by Yvan Adam offers a drawing of what was on their table. Inside, the booklet provides no explanations for the songs. It simply contains the lyrics in white font on a black background with faint grey doodles from the band members and their neighbours. The album looks as though it is a product of their communal living. The working class table spread depicted on the back and the do-it-yourself nature of the doodles give the album a sense of honesty and depict a very different Quebec than those to whom the political elite of the sovereignty movement catered.

The ten tracks on the album range from topics of explicit socio-political importance such as violence against children (“Dédé”), commercialization (“La Rue Principale”), homelessness (“Passe-Moé La Puck”), and HIV/AIDS (“Sérépositif Boogie”) to more darkly comedic character pieces (“Mauvais Caractère,” “Je Chante Comme Une Casserole”) and songs about love (“Julie”) and its troubles (“Just Une P’tite Nuit”). Different fans and critics are bound to pick different songs as defining the album based on subject matter or commercial success. For me, two stand out in particular as examples of the class-consciousness Les Colocs bring to their music. These are “Dédé” and “Passé-moé la puck.”

In “Dédé,” the album’s opening track, Fortin puts himself in the position of a child victim of poverty and violence, a character who shares his name. The lyrics tell the story of an ill-treated child whose biological dad is an alcoholic and non-biological mother, a prostitute, and who finds his solace in playing amongst the garbage in the alleyways. Offering a sort of sympathy to the noise and folly of the child who cannot chase the demons from his head, the musical bridges include tap dancing and the onomatopoeia of the choruses bring a certain joy to the already fun and rhythmic music on the track.

The misfortune of the poor is again the subject in “Passé-moé la puck”, but this time Fortin focuses on being without work or a home. Using the metaphor of hockey for the title and chorus, the song’s title alludes to the fact that without access to a puck, you cannot score in hockey, just as the way the lack of resources and barriers imposed on those who are marginalized prevents them from having a fair chance in life. The track opens with a mix of acapella scat with monkey-like noises and maintains high energy throughout with an eclectic mix of musical elements: rap-like singing style, rock guitars, a break for a fiddle, feet, a harmonica musical bridge, and even a kind of wailing scat. This, combined with a heavy use of irony in the lyrics has the effect of taking a rather humorous approach to a serious subject. The satirical socio-political critique directly takes on the opportunists of his day: journalists, city hall officials, and then municipal mayor Jean Doré, “Golden Johnny.” Strong guitar licks and jerky harmonica lines make the satire of the lyrics all the more poignant.

|

|

Directors: André Fortin and Patrick Lanthier 23 mai 1993 |

Reception and impact

A mere week after its release, Les Colocs’ debut album already figured in the Top 20 for Quebec sales and the album's single “Julie” was in twelfth position in the charts on Radio Activité (Québec Info Musique 2014). The album went on to reach platinum status in Canada selling 150,000 copies. In October 1993, they won four Félix Awards, including one for group of the year and one for revelation of the year (Gagnon 2009). It was a commercial success and there was peer recognition that what they were doing was special.

Though Les Colocs would go on to produce two more albums with a changing lineup, Esposito’s death in November 1994 marked a changing point and Fortin’s suicide in 2000 marked the end of the group. It is difficult to disaggregate the influence of the 1993 debut album from Les Colocs’ later work, because what Les Colocs have come to represent includes their later album Dehors Novembre and a whole spectrum of speculation around Fortin’s suicide and what could have been.

What is clear, however, is that Les Colocs opened up mainstream media and cultural coverage, in much more sympathetic ways, to issues that were not included before such as homelessness, domestic violence, depression, and AIDS. Their 1993 album came out before the internet revolutionized the music industry, when traditional sources of music from shops to radio stations still exercised a monopoly. Because their music spoke to a sizeable, largely young audience, they managed to attain commercial success with a class-conscious form of Quebec chanson.

Les Colocs’s debut album was an ode to life in all its daily and difficult forms. At a time when there was a dearth of Quebec songs in the music charts, they brought an invigorating energy that set the stage for much of what was to come. Five roommates in a crumbling flat on St. Laurent managed to broaden the identity expressed in Quebec chanson by presenting music that was first and foremost fun and which engaged with the taboos of poverty, violence, addiction, and disease. In so doing, they created something qualitatively different from the generations before them and set the stage for later groups like Loco Locass and Les Cowboys Fringants. Les Colocs brought a new, more diverse kind of Quebec francophone identity to music.

Though Les Colocs would go on to produce two more albums with a changing lineup, Esposito’s death in November 1994 marked a changing point and Fortin’s suicide in 2000 marked the end of the group. It is difficult to disaggregate the influence of the 1993 debut album from Les Colocs’ later work, because what Les Colocs have come to represent includes their later album Dehors Novembre and a whole spectrum of speculation around Fortin’s suicide and what could have been.

What is clear, however, is that Les Colocs opened up mainstream media and cultural coverage, in much more sympathetic ways, to issues that were not included before such as homelessness, domestic violence, depression, and AIDS. Their 1993 album came out before the internet revolutionized the music industry, when traditional sources of music from shops to radio stations still exercised a monopoly. Because their music spoke to a sizeable, largely young audience, they managed to attain commercial success with a class-conscious form of Quebec chanson.

Les Colocs’s debut album was an ode to life in all its daily and difficult forms. At a time when there was a dearth of Quebec songs in the music charts, they brought an invigorating energy that set the stage for much of what was to come. Five roommates in a crumbling flat on St. Laurent managed to broaden the identity expressed in Quebec chanson by presenting music that was first and foremost fun and which engaged with the taboos of poverty, violence, addiction, and disease. In so doing, they created something qualitatively different from the generations before them and set the stage for later groups like Loco Locass and Les Cowboys Fringants. Les Colocs brought a new, more diverse kind of Quebec francophone identity to music.

Sources

Bilodeau, Michel. 1993. "Ce Phénomène Appelé «Colocs». Le Soleil. 14 March 1993.

Gagnon, Annie. 2009. "André (Dédé) Fortin." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada.

Ledoux, Julie. 2010. “L'âme Escogriffe Des Colocs : Ironie Et Critique Sociale Dans La Chanson Québécoise Engagée”. Thesis: Université De Montréal.

Les Colocs. Site Officiel.

Québec Info Musique. "Les Colocs."

Musimax. 2001. André “Dédé” Fortin: La Biographie, 9 May 2001.

Paquin, Raymond. 2004. Dédé. Montréal: Quitte Ou Double.

Peron, Gilles. 2007. "La Chanson Québécoise De L’Osstidcho à Aujourd’hui." Québec Français, vol.145, no. 54-56.

Roy, Bruno. 1991. Pouvoir Chanter. Montréal: VLB éditeur.

Sweeny, Robert. 2014. Telephone interview. 2 Nov. 2014.

Vigneault, Alexandre. 2013. "Les Colocs En Cinq Chansons." La Presse, 15 June 2013.