The Fair Sex as an Entertaining Companion: Music Dissemination and Women in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-century England

Par Susanne Sevcik

The musical activities of English women in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries provide a rich ground for exploring how music can enable or restrict marginalized groups. Musical conventions in early modern England were often limiting for women, rendering their voices faint, if not silenced. Yet, primary sources referencing these women can uncover a nuanced context for women’s music making that engages perspectives oftentimes invisible or dismissed within traditional university music settings.

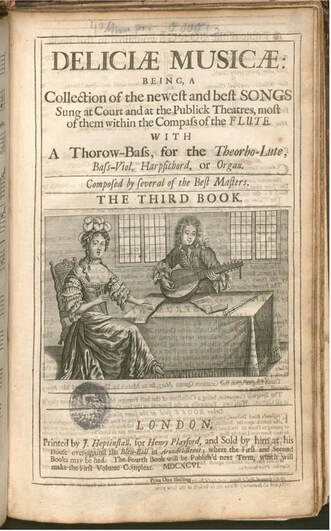

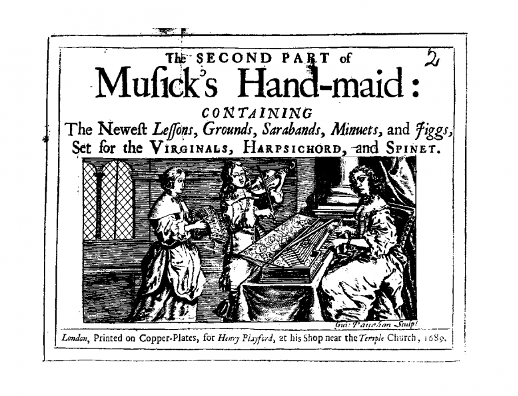

Figure 1: Front cover of John Playford’s Musicks Hand-Maid (1689) showcasing

Figure 1: Front cover of John Playford’s Musicks Hand-Maid (1689) showcasing women accompanying a male amateur musician. Source: John Playford, “Musick’s

Hand-Maid”, 1689. IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download.

The interplay of culture and context situates early modern English women into a distinct positionality combining class, wealth, education, skill set, and environment. These restricted positions were confounded by economic and social barriers that limited their access to music-making, and circularly, this lack of access often reinforced the societal expectations and constructs placed on English women as a means of social control. I examine three secondary sources that consider primary sources to elaborate this complexly restrictive environment demarcated by the culture surrounding the commercialization of music (Carter 2016), the lasting legacy of music scores tailored to women (Miller 2017), and the activity of music student Elizabeth Rogers (Bailey 2008). The application of a gender framework reveals key perspectives: how amateur women musicians were intentionally left out of the narrative, how their involvement was restricted, or at times, as seen through the Elizabeth Rogers Hir Virginall Book (c.1657; Bailey 2008), how boundaries were extraordinarily blurred. These perspectives create a model that can inform a gender conscious scholarly approach to early music.

Women excluded from the narrative

Women restricted by boundaries

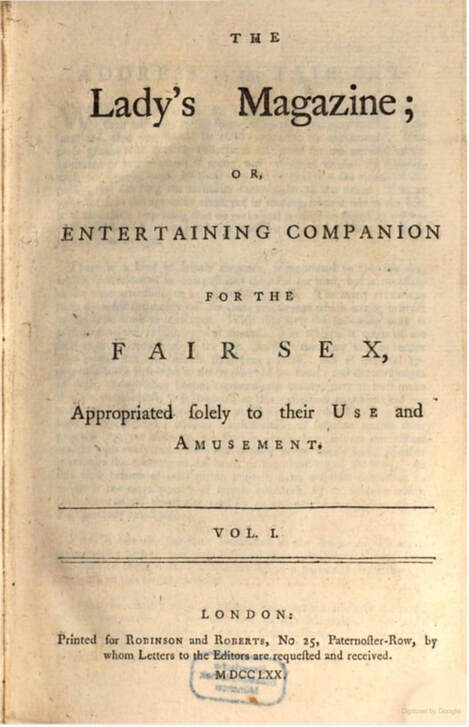

Figure 3: The front page of the first edition of The Ladys Magazine, 1770.

Figure 3: The front page of the first edition of The Ladys Magazine, 1770. Source: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy, “The Lady’s Magazine or Entertaining

Companion for the Fair Sex”, 1770. London: Robinson and Roberts.

Nearly a century later, printed music gained greater traction with the first edition of The Lady’s Magazine printed in 1770. Bonny Miller notes the double-sided nature of the magazine's dedication to “the fair sex's use and amusement,” asserting that “while the magazine cultivated British woman’s education, each page also presented models to construct her opinions and conduct” (Miller 2017, 240). On the back of every edition there was a sheet of music, but the type of music shared was restricted to three categories: songs of love, pastoral songs, and songs of British nationalism (Leslie Richie as cited by Miller 2017, 240).

Outside of the home, women commonly encountered music in the popularized pleasure gardens where men and women would parade around and court each other. Not surprisingly, many of the lyrics for these love songs included suggestive language with double-entendres that were clearly censored in the publications for women; “lyrics that were too suggestive of inappropriate sentiments or behaviour were revised into inoffensive pastoral verses” so that women could hear the lyrics when accompanied by a man but never reproduce them on her own (Miller 2017, 240). This music was often patronizing in that “it preserves [Ladies] from the Rust of Idleness, that most pernicious Enemy to Virtue” with common sexist misconceptions that “indelicate language” would convey “a train of luscious ideas, as are only calculated to foil the purity of a youthful mind” (1772 conduct book; Rev. John Bennett as cited and discussed in Miller 2017, 241-42).

Outside of the home, women commonly encountered music in the popularized pleasure gardens where men and women would parade around and court each other. Not surprisingly, many of the lyrics for these love songs included suggestive language with double-entendres that were clearly censored in the publications for women; “lyrics that were too suggestive of inappropriate sentiments or behaviour were revised into inoffensive pastoral verses” so that women could hear the lyrics when accompanied by a man but never reproduce them on her own (Miller 2017, 240). This music was often patronizing in that “it preserves [Ladies] from the Rust of Idleness, that most pernicious Enemy to Virtue” with common sexist misconceptions that “indelicate language” would convey “a train of luscious ideas, as are only calculated to foil the purity of a youthful mind” (1772 conduct book; Rev. John Bennett as cited and discussed in Miller 2017, 241-42).

However, this magazine was not merely a means for social control—it also liberated women by exposing them to music previously restricted to the semiprivate societies of privileged male amateurs (Miller 2017, 249). Moreover, it featured one female composer among the frequently issued composers’ works: Elizabeth Turner (d. 1756). This was a remarkable act of respect coming from the editor who deemed her compositions just as worthy of publication as those of her male contemporaries.

Figure 4: Image of an 18th-century pleasure garden in London. Johann Sebastian Müller (engraving)

and Samuel Wale (painting), “View of the Grand Walk at the entrance of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens with

the orchestra playing”, 1751. Source: David Blackwell, “The Pleasure Gardens of 18th Century London”,

American Guild of Organists (AGO), 2013.

and Samuel Wale (painting), “View of the Grand Walk at the entrance of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens with

the orchestra playing”, 1751. Source: David Blackwell, “The Pleasure Gardens of 18th Century London”,

American Guild of Organists (AGO), 2013.

Women blurring boundaries

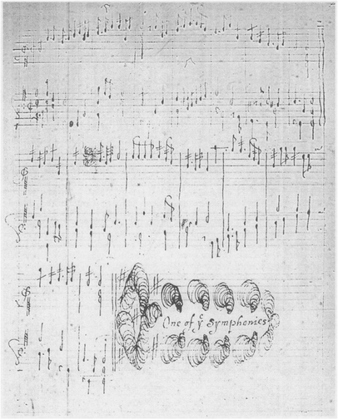

Figure 5: Excerpt from Elizabeth Rogers hir virginall

Figure 5: Excerpt from Elizabeth Rogers hir virginall book (Bailey 2008, 526). Elizabeth Rogers, “Elizabeth

Rogers hir virginall book”, 1657. London. MS 10337,

fo. 5, The British Library.

While these examples underscore restrictions to women’s musical access, outliers as evidenced by Elizabeth Rogers hir virginall book (c.1657), suggest that there were in fact women who “received training in composition, transposition, and ornamentation, a possibility that broadens our interpretation of women and musical education in England at this time” (Bailey 2008, 510-511). While printed music in the seventeenth century centered on male amusement, evidence from Rogers’ lesson book suggest a more expansive narrative. Candace Bailey uses the analysis of this primary source to ask if women like Rogers can be considered professional musicians? (Bailey 2008, 516). While their career paths indicate otherwise, their skill set, accomplishments and creations suggest that their activity was of professional level. Regardless, women at this time admirably blurred the lines between amateur and professional music study in spite of their limited domestic environment.

As this evaluation of primary sources reveals, the forces that both hindered and enabled the agency of women musicians in early modern England are more nuanced and complex than usually understood. The realms of novel printing technologies, pleasure gardens, and domestic education increased the accessibility of music to women while simultaneously controlling them socially. Engaging with this nuanced position of women and music can productively disrupt embedded canonic narratives that dismiss their contributions and account for women’s stratified participation. Although they were intentionally left out of the narrative in early printed scores and their access to music was restricted through censorship in the eighteenth century, like Elizabeth Turner and Elizabeth Rogers, and against all odds, they defied boundaries of what it meant to be the ‘fair sex’. In understanding these boundaries, we can respect women’s agency in all its complexity.

As this evaluation of primary sources reveals, the forces that both hindered and enabled the agency of women musicians in early modern England are more nuanced and complex than usually understood. The realms of novel printing technologies, pleasure gardens, and domestic education increased the accessibility of music to women while simultaneously controlling them socially. Engaging with this nuanced position of women and music can productively disrupt embedded canonic narratives that dismiss their contributions and account for women’s stratified participation. Although they were intentionally left out of the narrative in early printed scores and their access to music was restricted through censorship in the eighteenth century, like Elizabeth Turner and Elizabeth Rogers, and against all odds, they defied boundaries of what it meant to be the ‘fair sex’. In understanding these boundaries, we can respect women’s agency in all its complexity.

Wanda Landowska, “Elizabeth Rogers' Virginal Book: No. 20, The Nightingale”, 1958. Les chefs-d'œuvre du clavecin (Mono Version), Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2016 collection. Youtube video.

Bibliography

BAILEY, Candace. 2008. “Blurring the Lines: ‘Elizabeth Rogers Hir Virginall Book’ in Context.” Music & Letters, vol. 89, no. 4 (November 2008): p. 510-46.

BENNETT, John. 1789. “Letters to a Young Lady, on a Variety of Useful and Interesting Subjects: Calculated to Improve the Heart, to Form the Manners, and Enlighten the Understanding.” London; Newburyport, MA: John Mycall, [1792]. HathiTrust Digital Archive (accessed November 21, 2013).

CARTER, Stephanie. 2016. “‘Yong Beginners, Who Live in the Countrey’: John Playford and the Printed Music Market in Seventeenth-Century England.” Early Music History, vol. 35 (October 2016): p. 95-129.

ESSEX, John. 1722. “The Young Ladies Conduct: Or, Rules for Education, under Several Heads; with Instructions upon Dress, Both before and after Marriage. and Advice to Young Wives.” London. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (accessed November 29, 2013).

MILLER, Bonnie H. 2017. “Education, Entertainment, Embellishment: Music Publication in the Lady’s Magazine.” In Beyond Boundaries: Rethinking Music Circulation in Early Modern England, edited by Linda Phyllis Austern, Candace Bailey and Amanda Eubanks Winkler. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 238-56.

BENNETT, John. 1789. “Letters to a Young Lady, on a Variety of Useful and Interesting Subjects: Calculated to Improve the Heart, to Form the Manners, and Enlighten the Understanding.” London; Newburyport, MA: John Mycall, [1792]. HathiTrust Digital Archive (accessed November 21, 2013).

CARTER, Stephanie. 2016. “‘Yong Beginners, Who Live in the Countrey’: John Playford and the Printed Music Market in Seventeenth-Century England.” Early Music History, vol. 35 (October 2016): p. 95-129.

ESSEX, John. 1722. “The Young Ladies Conduct: Or, Rules for Education, under Several Heads; with Instructions upon Dress, Both before and after Marriage. and Advice to Young Wives.” London. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (accessed November 29, 2013).

MILLER, Bonnie H. 2017. “Education, Entertainment, Embellishment: Music Publication in the Lady’s Magazine.” In Beyond Boundaries: Rethinking Music Circulation in Early Modern England, edited by Linda Phyllis Austern, Candace Bailey and Amanda Eubanks Winkler. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 238-56.